Internal Expansions

For many different reasons, a great deal of music written in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries exhibits metric patterning, at many different levels of hypermeter, that is duple in structure. Such was the tendency in the nineteenth century that William Rothstein, in Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music, has memorably dubbed this "the Great Nineteenth-Century Rhythm Problem." It is "a danger," Rothstein says,

endemic in 19th-century music, of too unrelievedly duple a hypermetrical pattern, of too consistent and unvarying a phrase structure—the danger, in short, of submitting too complacently to 'the tyranny of the four-measure phrase.'

Music in the classical tradition was quite often less subservient to the two- and four-bar units. While this topic has been the subject of a great deal of musical theoretical exploration, here we will concentrate on a simple and common type of sub-phrase and phrase expansion.

# Sub-phrase Expansion

When a two-measure basic idea or contrasting idea is expanded, that expansion is often accomplished through motivic repetition within the basic idea: a motive or other small melodic figure is repeated, either exactly or with simple embellishment, causing the overall length of the sub-phrase to be larger than the expected.

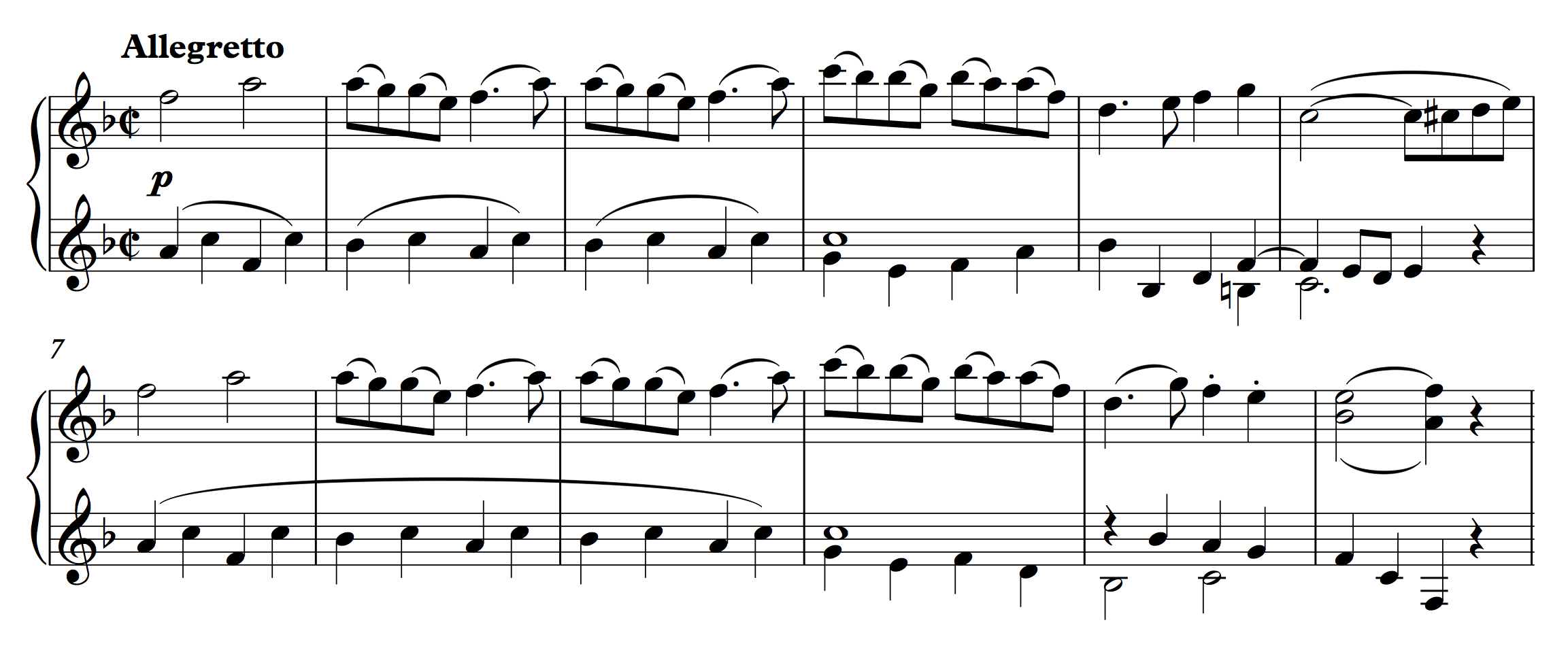

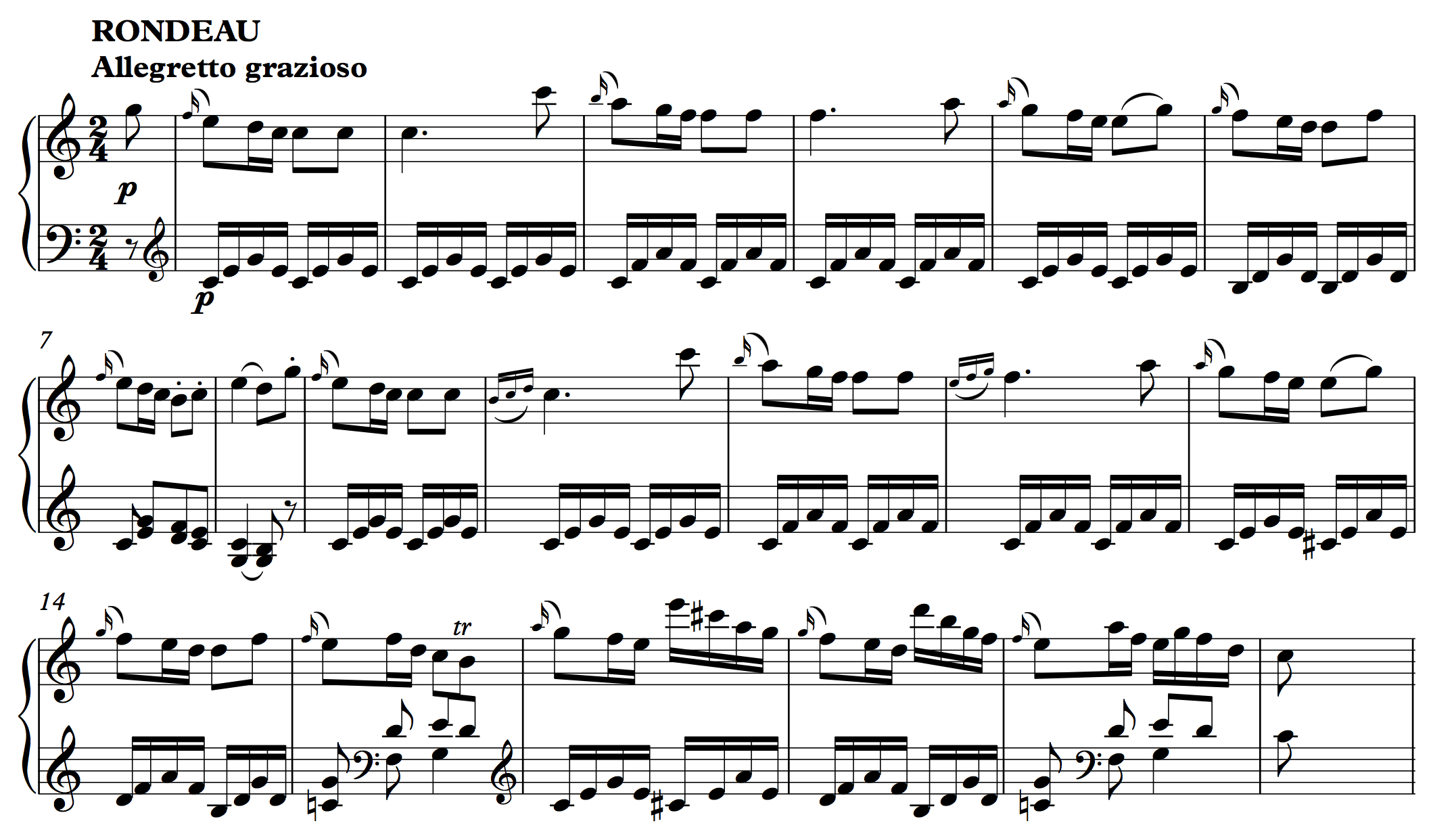

Mozart's Rondo in F begins with a period. A half cadence in m. 6 is followed by a consequent phrase that ends with a PAC in m. 12. The theme’s exceptional length is caused in part by an expansion of the initial basic idea: in m. 3, the piano repeats m. 2. One could imagine a simple recomposition of the passage, omitting m. 3, that would restore the sub-phrase to a normal, 2-bar length.

The contrasting idea is also three bars long. But in this case, it is less clear if the greater length is due to expansion. There is no repetition, and it's difficult to imagine a two-measure recomposition of the contrasting idea that wouldn't destroy some aspect of its melodic or harmonic structure.

In other words, irregular lengths don't always indicate that an expansion has occurred.

# Phrase Expansion

Phrases are often expanded by repetition as well—most often in the concluding portion of a theme as a means to delay cadential arrival.

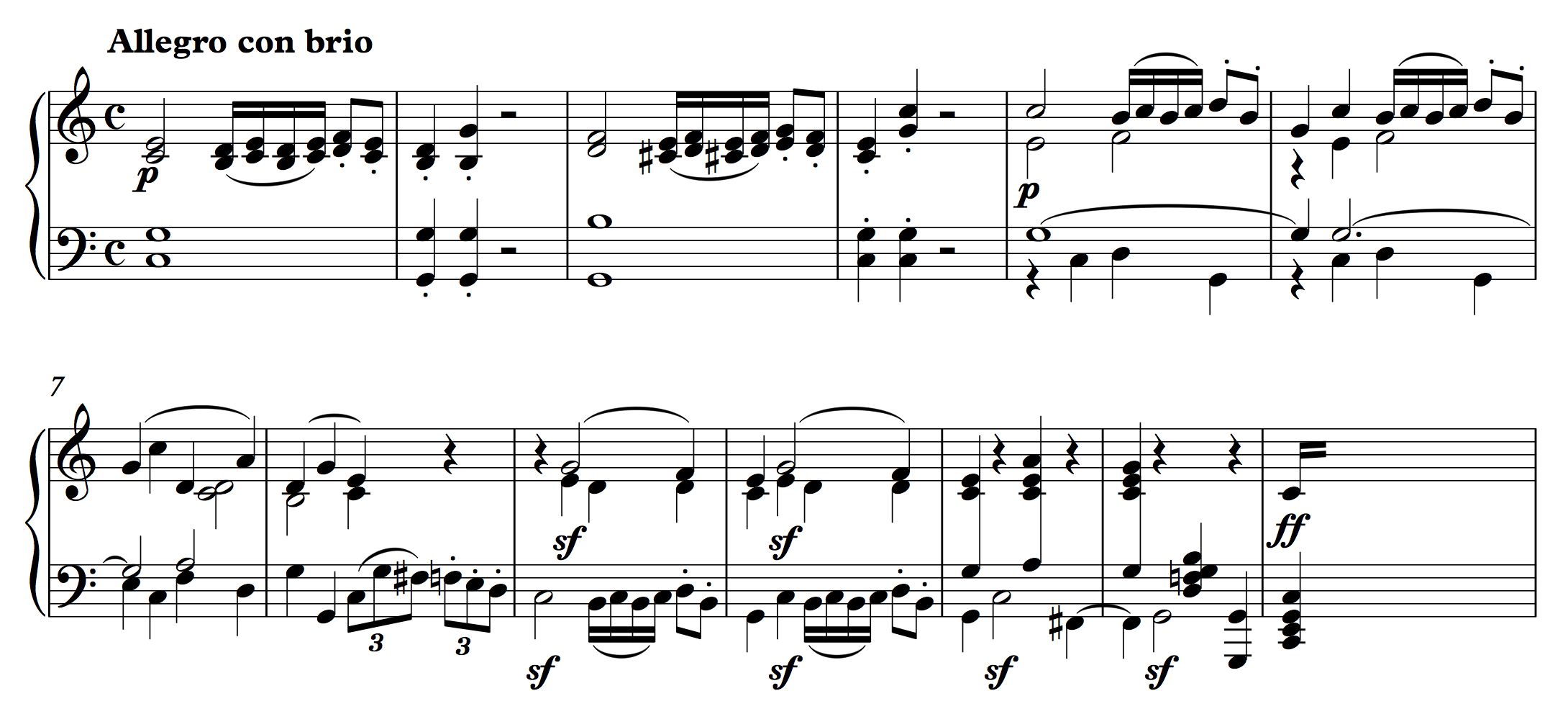

The main theme's first eight measures form a simple sentence. But at the moment of expected PAC in m. 8, the melody find scale degree 3, creating an IAC. At the same time, the bass plays a descending link into a repetition of the continuation that leads to a PAC in m. 13. This phrase expansion, thus, adds five measures to the length of the basic phrase.

In the example above, the cadence in m. 8 gave rise to an expansion because as it was weaker than expected. (Primary themes rarely conclude with IACs.) This is one of the most common musical motivations for a phrase expansion. In addition to IACs, deceptive cadences can lead to expanded phrases, and not uncommonly, an expected cadence never materializes at all—an event often called an "evaded cadence."

The primary theme of this sonata is a compound period made from two sentences. Following the half cadence in m. 8, the large consequent is expected to conclude with a PAC in m. 16. But the PAC never materializes: the leading tone in m. 15 is not resolved, the pianist's right hand leaps up to A5 instead. The cadence, in other words, is evaded. The next four measures (mm. 16–19) are a varied repeat of mm. 13-15, "one more time," culminating in a PAC in m. 19.

# Non-standard Lengths

We often find expansions in places where the size of a sub-phrase or phrase has been increased. The phrase expansion described above created an 11-bar continuation, for example. But irregular phrase lengths do not necessarily indicate the presence of a phrase expansion.

For example, listen a few times to the first 30 seconds of the following passage, from Mozart's String Quintet in C major, K. 515. Its main theme is a compound sentence. The theme's presentation has three basic ideas (at 0:00, 0:09, and 0:16), each of which is constructed as a compound basic idea that contains a basic idea followed by a contrasting one:

We hear in this passage that the compound basic ideas are five measures long, each basic idea itself lasting three measures! But no phrase expansion has occurred here. The basic idea is simply longer than normal, and perhaps a bit looser feeling as a result. When in doubt, the central question is whether a passage might be recomposed, duple-fied without destroying its melodic, harmonic, and motivic structure. If you can, there is a case to be made that an expansion is present.