Set Class and Prime Form (2)

Analytically, the concept of set class is useful because it can show coherence in a composition. Bartók's "Subject and Reflection," for example, uses the (02357) set class nearly exclusively—though it appears in many transpositions and inversions.

Theoretically, the concept is useful because it provides a prism through which we can begin to study the possibilities provided to us by the twelve pitch-class universe. For almost 500 years, composers mostly used only a small subset of those possibilities (triads, seventh chords, and so forth). Set class lists reveals all of the other possibilities. They also give us hints as to why tonal composers used only a small portion of them and suggest entire worlds organized through other means. Fortunately for us, we don't need to create such a list because many others have!

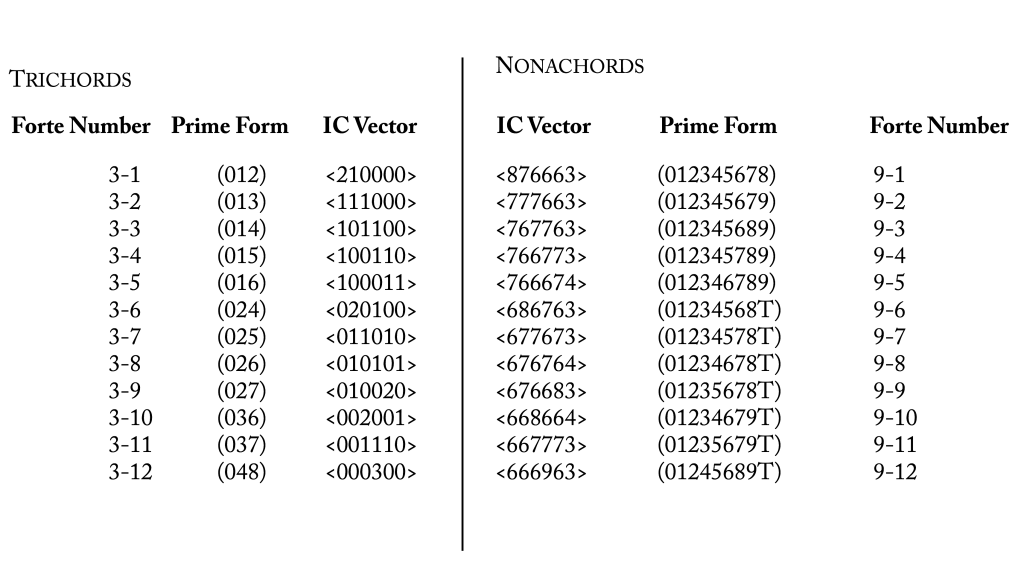

Most of these set-class lists are organized similarly. Set classes that have the same number of notes in them (we say that they have the same "cardinality") are grouped together: trichords (three-note pitch-class sets) sit together, as do nonachords (nine-note pitch-class sets), and so on.

Prime form for each set class is show in parenthesis. The "Forte Number" (3-1, 9-1, etc.), often adjacent to the prime form, was given to each set class by the famous music theorist Allen Forte, who was one of the first to describe the set class list.

# Interval Class Vector

The interval class vector next to each set class's prime form is particularly valuable. Think of it as a numeric representation of the "intervallic flavor" of each set class. IC vectors have six places <_ _ _ _ _ _> that are placeholders for interval classes 1–6. If a set class has a single interval class 1, it will have the digit 1 in the interval class vectors first placeholder. The IC vector <001110>, for example describes a trichord with 1 interval class 3, 1 interval class 4, and 1 interval class 5; that is, the major or minor triad, set class (037)!

Note: broken links have been removed and not replaced.